China's hydropower grab in the Himalayas

A new dam on the Brahmaputra River will pose a massive threat to India and Bangladesh.

In July 2020, Indian and Chinese troops were involved in a border skirmish high in the Himalayas that killed 20 Indian soldiers, and a likely similar number of Chinese troops. The fighting led to relations between the two countries dropping to their lowest point in decades. Despite this, the area they were fighting over - the Galwan River Valley - sits high in the Himalayas, a barren and inhospitable ground that holds only nationalistic value for either side.

But what if China gave India a real reason to fight for its mountainous northern border?

Enter China’s 14th Five-Year Plan…

In Section 14, Chapter 2, under the heading “Expanding Investment Space” a single sentence is mentioned which could have explosive consequences for India. “Promote the construction of major projects such as new infrastructure, new urbanization, and transportation and water conservancy [...] implement [...] the downstream hydropower development of the Yarlung Zangbo River…”

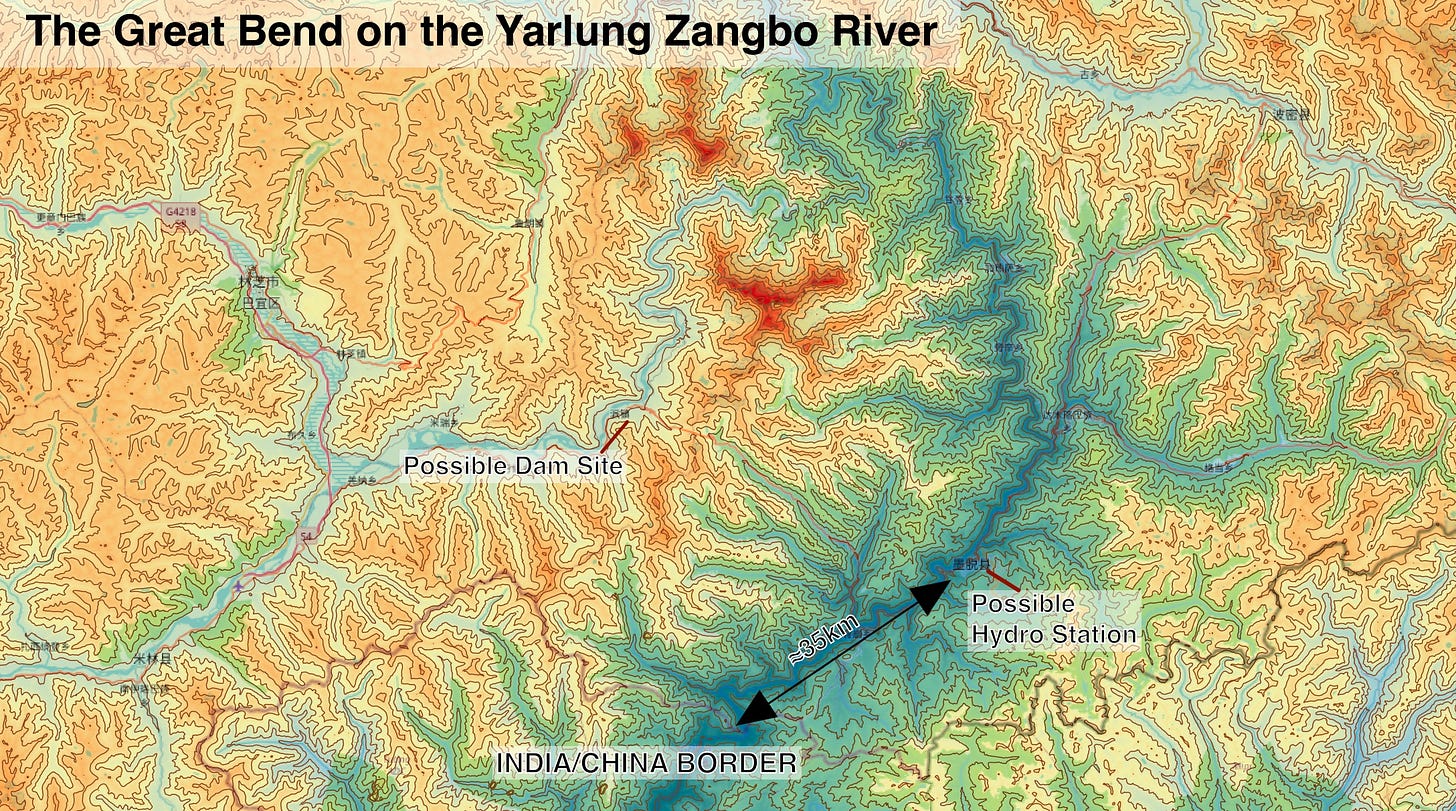

This single sentence serves as confirmation that China is going ahead with a long-discussed plan to build a massive hydropower project on what it calls the Yarlung Zangbo River - the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra River. At a location known as the ‘Great Bend’, the river’s course takes a u-turn from north to south, as it passes through one of the deepest canyons in the world. Here, the water drops from about 2,900 metres to an elevation of 660 metres when it crosses into India, giving this region perhaps the greatest hydropower potential of anywhere on Earth.

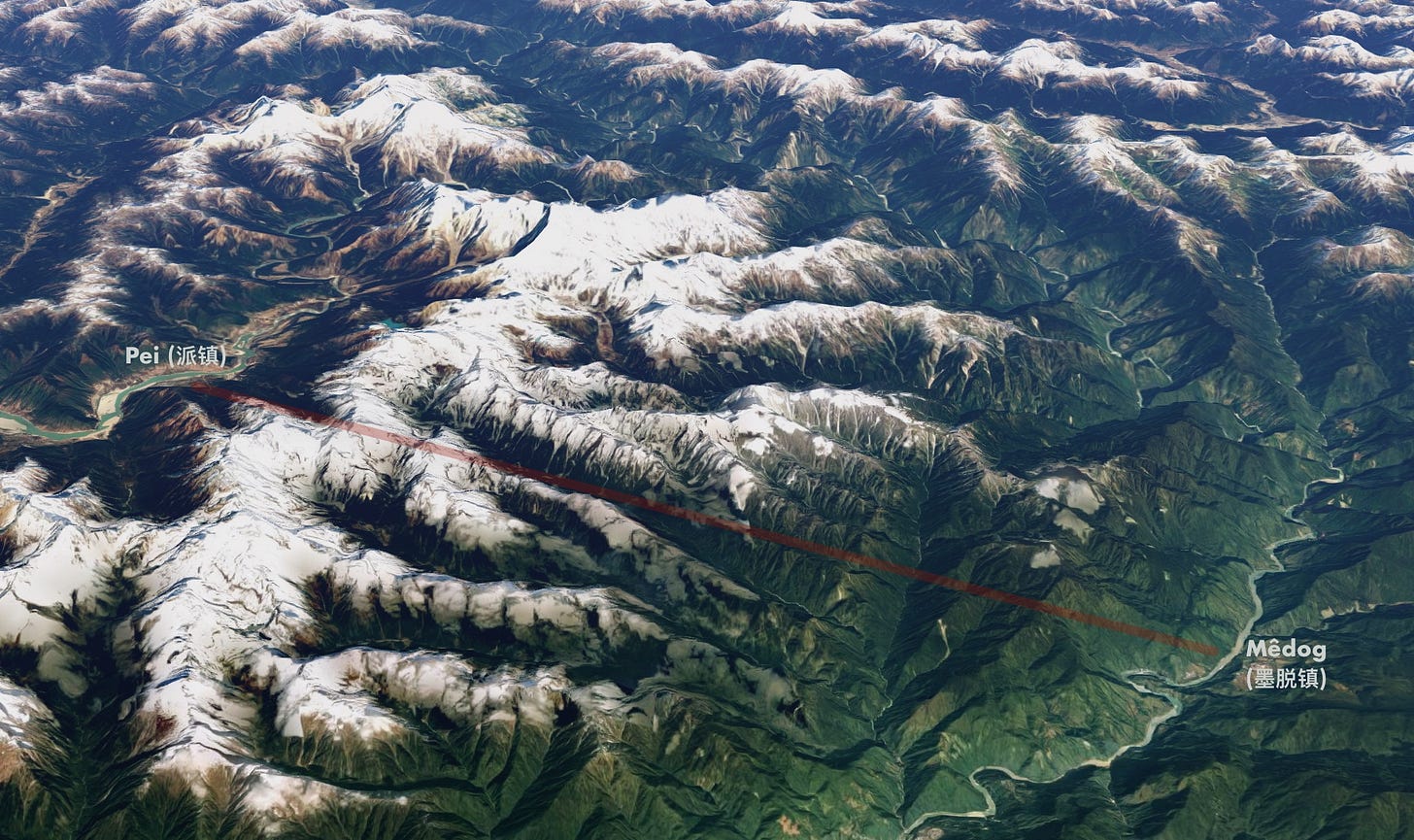

And it is with this huge energy potential difference that China plans to build a hydropower system that would eventually have 60GW in generating capacity - almost three times that of the Three Gorges Dam, the largest in the world. Little is known how China specifically plans to implement this, however one proposal that has been discussed in the past, involves the construction of a tunnel, which would cut the Great Bend, and drop 2000m in height, allowing for massive power generation at the bottom. Such a tunnel would likely have its entry point near Pei Town (派镇), and its terminus near Mêdog Town (墨脱镇), just 35km upstream from the Indian border. As such, this would necessitate the construction of a large dam near Pei, which would cause substantial upstream flooding including the city of Nyingchi (林芝市) and necessitate the evacuation of hundreds of thousands of people.

Nonetheless, it is the downstream impacts that are far more concerning. The Brahmaputra River delivers a large portion of the water used by India’s North Eastern Region (NER) and approximately 60 percent of the population of Bangladesh lives within its basin. While more than 50 percent of the river’s total catchment area is within Chinese territory (mostly in Tibet), the portion of the total flow that begins in China is not well researched. A paper by CNA notes that the low estimate is 7 percent, while the high estimate is 40 percent. Seasonal variation is also an important factor, and the project would effectively make India and Bangladesh dependent on China for the release of water during the dry season, and for protection from floods during the wet season.

While China promotes making “efforts to deepen mutual trust and cooperation on shared water resources”, it is not a state party to the UN Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, and in the past has suddenly cut the flow of water from its dams to downstream nations. Recently, in December 2019, flow from the Jinghong Dam on the Mekong River was cut, resulting in a massive loss of water downstream in Thailand during an ongoing drought. In January this year, the cut was carried out again, with Chinese authorities only giving downstream countries notice days after the flow was reduced.

These practices make the construction of a dam on the Yarlung Zangbo/Brahmaputra River a massive problem for India and Bangladesh. Adding to the concern of these countries is the language Chinese officials are using to discuss the dam. Yan Zhiyong, chairman of the Power Construction Corp of China, noted in the state-run Global Times:

"…it will be a historic opportunity for the Chinese hydropower industry [...] it is a project for national security, including water resources and domestic security.”

The fact that this dam is seen as having a national security element suggests that it may be used as a political tool. In periods of high tension, such as the recent border dispute along the Galwan River, China could cut water in order to extra concessions. Moreover, in the event of a more serious conflict, water flow could be cut entirely. The location of the dam just before the border with India makes it perfect for such retaliation, as changes to the river flow would have almost no impact on China. How India could retaliate to such a flow cut is unclear.

Another security issue is caused geology of the region itself. The Himalayas mountains are the result of the ongoing collision of the Indian and the Eurasian Plates, something which generates massive amounts of stored up energy. This energy is periodically released in the form of earthquakes. History shows the construction of dams in this region is a disaster waiting to happen. Four major earthquakes, measuring 7.8 to 8.7 on the Richter scale, occurred within a span of 53 years between 1897 and 1950. The first and last of these occurred immediately south and west of the Great Bend, very close to the likely site of the new mega-dam. Should any dam on the Yarlung Zangbo collapse, it would likely cause massive flooding downstream, likely killing many and destroying significant amounts of infrastructure in India and Bangladesh. Again, however, the consequences would be only minimal in China, as the dam would be so close to the border.

Taken together it appears likely that this hydropower project will become a future flashpoint for conflict, particularly between India and China. Much like the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Nile, it threatens downstream countries while posing only minimal risk to its parent nation. Similarly, the size of the project will make it an unstoppable juggernaut once construction begins. And, as in Ethiopia, the expected water shortages caused by climate change also make conflict more likely, as China, India and Bangladesh attempt to capture the last of the water from the mighty Himalayan glaciers before they melt.